Massachusetts can’t afford to lose Haitian caregivers

Massachusetts can’t afford to lose Haitian caregivers

Uncertainty for Haitian Workers

Uncertainty for Haitian Workers

TPS status for nearly 45,000 Haitians in Massachusetts is set to end on February 3rd.

Earlier this week, the Home Care Alliance distributed a brief member survey to better understand the potential impact this could have on our membership.

Based on the results, the Alliance estimates that between 800 and 1,000 workers across our member agencies could be affected. That number is likely higher when accounting for non-member agencies and home care workers in other programs, such as the self-directed PCA program, as well as workers in settings like nursing homes and hospitals.

As I’ve conveyed to members of the Healey administration, even an agency losing one or two workers can have a significant impact—when each caregiver may provide two to five visits per day (12–20 visits per week). This would disrupt continuity of care and threaten the trusted relationships between consumers and their caregivers.

Please continue to keep me informed as we stay in close contact with the Healey Administration as this deadline approaches. Any information, powerful stories or data is helpful.

Jake Krilovich

Chief Executive Officer

Massachusetts can’t afford to lose Haitian caregivers

The February 3 TPS deadline isn’t just an immigration story. It’s an access-to-care story — and patients will feel it first.

In the living room of a Randolph apartment, a 3-year-old beams as he shows off his electric tricycle. His father, “Jacques,” a certified nursing assistant at a Boston-area hospital, smiles back — but he is afraid. His employer has told him he will be let go if he cannot secure a new immigration status before February 3.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Jacques told WBUR. “I have an apartment to pay, I have a car loan, and I have my family in Haiti to help.”

Jacques’ family is in the United States under Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a humanitarian program that allows people from countries in crisis to live and work legally. If TPS for Haitians expires on February 3, as currently scheduled, thousands of workers like Jacques could lose their jobs overnight.

For Massachusetts home care, the impact will not be abstract. It will be measured in canceled visits, disrupted care plans, and families suddenly left without help.

What the data shows

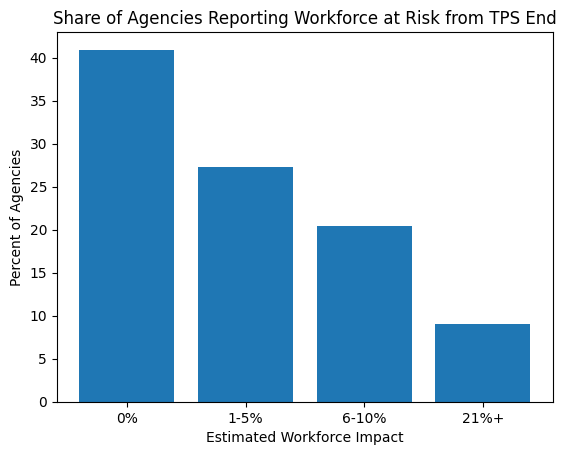

A new snapshot survey of 44 Massachusetts member home care agencies shows that nearly six in ten agencies would lose at least some of their direct-care workforce if TPS expires. And for one in ten agencies, the loss could exceed 21 percent of staff.

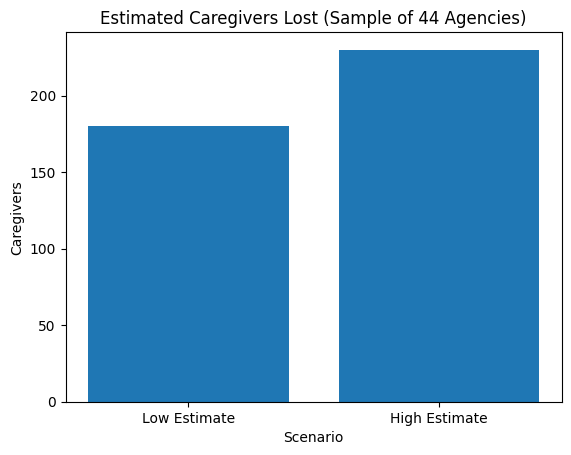

Taken together, the responding agencies employ an estimated 4,600 direct care workers in Massachusetts. Even using conservative assumptions, the data indicates that 180 to 230 caregivers could disappear from this small sample alone.

That loss translates into 2,160 to 4,600 home care visits per week — care that would simply not happen.

These findings mirror what providers across the state are already reporting. Dr. Asif Merchant, medical director at five Massachusetts nursing homes, told WBUR his facilities are bracing to lose 7 to 20 percent of staff if TPS ends. The Massachusetts Senior Care Association estimates that 2,000 caregivers statewide could be affected.

“This is not speculative,” Merchant said. “We are quite heavily reliant on these migrant workers. And suddenly a large portion of that will just evaporate.”

A workforce already at its limit

Home care agencies operate on razor-thin staffing margins. One missed shift can ripple through an entire day’s schedule. Losing dozens — or hundreds — of caregivers at once would push many providers beyond their capacity to serve vulnerable patients.

In the survey:

- 27% of agencies said 1–5% of staff could be lost

- 20% said 6–10%

- 9% said 21% or more

The risk is uneven — and that is what makes it dangerous. Some agencies may feel little impact, while others could face losses large enough to force service reductions or closures. Entire communities could suddenly lose local providers.

What 200 caregivers really means

In home care, one caregiver typically supports 2 to 5 client visits per day — or 12 to 20 per week.

If 180 caregivers are removed from the system, that is more than 2,000 missed visits each week.

At the high end, 230 caregivers would mean nearly 5,000 visits lost every week.

These are not abstract numbers. They represent:

- Missed medication reminders

- Skipped meals

- Delayed bathing and mobility assistance

- Exhausted family caregivers forced to fill gaps

When home care fails, emergency rooms and hospitals feel it next.

180–230 caregivers could be lost — erasing thousands of visits weekly.

A silent system shock

Unlike hospitals, home care has no surge capacity. There is no waiting list to draw from, no reserve workforce. When workers disappear, cases are dropped, hours are reduced, and families are told to wait — or find care elsewhere. Often, there is nowhere else to go.

Even before the February deadline, providers report workers leaving preemptively out of fear and uncertainty. That “quiet exit” may be just as damaging as a formal termination.

What happens next

Unless TPS is extended, thousands of Haitian health care workers across Massachusetts could lose authorization to work on February 3. For home care, this would not be a slow squeeze. It would be an immediate capacity collapse.

The numbers are small enough to ignore —

and large enough to destabilize the system.

And they are coming fast.